In This Story

As this unusual fall semester ends, we wanted to take the opportunity to talk to several George Mason University professors who taught in-person or hybrid classes. Here are their thoughts on what worked well for them.

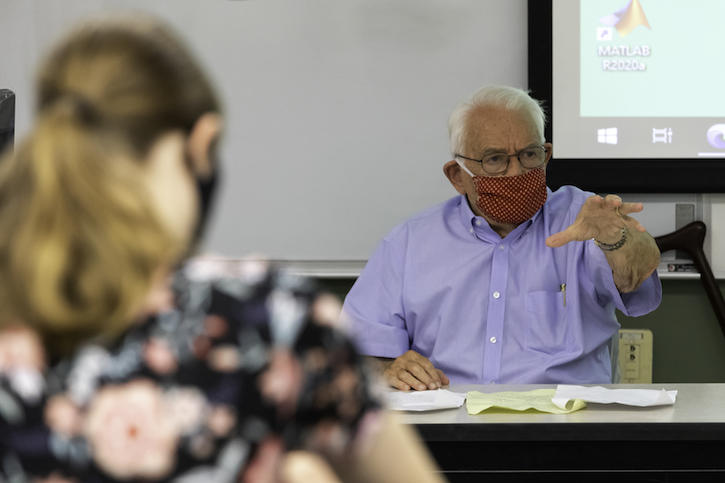

During a career in higher education spanning almost six decades, in dozens of positions at five universities, Peter Stearns has been through it all—calming nervous freshmen, developing new educational strategies, supporting stressed doctoral candidates, and navigating the myriad administrative challenges as Mason’s provost for 14 years.

Teaching and learning during a pandemic was a predicament that provided new challenges for Stearns.

Nevertheless, he jumped in when the call went out for faculty interested in teaching face-to-face for Fall 2020.

“My daughter, who is a doctor, advised me not to do this,” he added. “But I saw this as a legit opportunity to pitch in.”

Any remaining concerns Stearns harbored regarding teaching face-to-face evaporated when he arrived at his Honors 240 classroom in Robinson Hall B. While the room would normally be set for 40 students, it was laid out for 18.

“It’s a very well-organized arrangement,” Stearns said. “It was all done by Facilities. The other chairs are completely gone; wipes and hand sanitizer are provided.”

Stearns taught two history courses this semester, one in a hybrid format, and one completely online, and said they both went well.

The new requirement of regularly sanitizing classrooms has kept Kathleen Mulcahy, director of woodwinds in the School of Music, on her feet—literally. Because Mulcahy does a significant amount of one-on-one teaching and the rooms need to be sanitized, Mulcahy must change venues after each student.

“I’m doing a lot more moving around,” she said. “It's been an adjustment getting used to carrying my work and instruments between several different locations on campus, but it has been worth it."

Mulcahy said she did not hesitate to return to campus to teach this fall.

“I felt like our school did so much more research on safe options for teaching music than many other university music programs,” she said. “My colleagues at other schools were very impressed with the information I was receiving from our leadership. None had received anywhere near the level of support and research available to me.”

In addition to moving among classrooms, Mulcahy noted that there were very visible differences inside those classrooms. Ventilation was a key part of the School of Music research.

“They decided what rooms we could safely use,” she said. “We are in a larger space than normal. And the students are surrounded by plexiglass, because it isn't possible for them to wear conventional masks while blowing into an instrument.”

When the weather is nice, Mulcahy moved her classes outside.

Part of Mulcahy’s inclination to return to face-to-face instruction was founded in the earlier limitations of teaching music online.

“Zoom was not intended for use to teach music lessons,” she said, adding that “certain settings have now been upgraded; musicians all over the world are using it.”

The best part of returning to campus was the response Mulcahy received from the students.

“The students are so appreciative of the opportunity to play live and together,” she said. “I feel like they’re more appreciative of me, too, and they thank me every day.”

That student affirmation is echoed by Robinson Professor of Public Affairs Steven Pearlstein.

“The students really appreciate it,” he said. “They see that the professor is working hard to make the class possible.”

In fact, one student jokingly told Pearlstein that his class was the highlight of his social week.

Pearlstein added: “I really wanted to teach in person. I get a lot of energy from the students, and they get a lot of energy from me.”

Pearlstein’s Honors 131 classroom is fully equipped with microphones throughout the room and cameras on the walls.

“Chairs are arrayed like a traditional classroom,” he said. “[Facilities] put Xs on the floor, and arranged eight feet between each of them” to comply with physical distancing requirements.

The microphones allow students and Pearlstein to be heard clearly through their masks.

It was important to Pearlstein to maintain the same Socratic method format for this class that he has honed over the years. He credits the classroom he uses for the ability to deliver his lectures as he always has.

“When you teach a large lecture class it’s a little bit like performance art,” Pearlstein said.

During Pearlstein’s classes, a graduate student coordinates the technology and handles the slides, the microphones, the camera and links to Blackboard Collaborate.

“Tech and my support spent a long time together preparing for this class, and Blackboard Collaborate has been great,” Pearlstein said.

In his history class, Stearns also uses Blackboard Collaborate once a week to support small group projects. These group exercises also help students stay engaged.

“This gives students the opportunity for contact in a group setting,” he said.

This semester, Stearns noted an interesting phenomenon that he attributes to the lack of other activities during the students’ days.

“Some students are actually doing things better this semester,” Stearns said. “I think this classwork is the only thing they have to do—more students are turning in work early and the quality of work for the freshmen students is especially better than I’ve previously seen.”

That, according to Stearns, is a silver lining of this unprecedented semester.